NOTE: Find highlighted text or parts

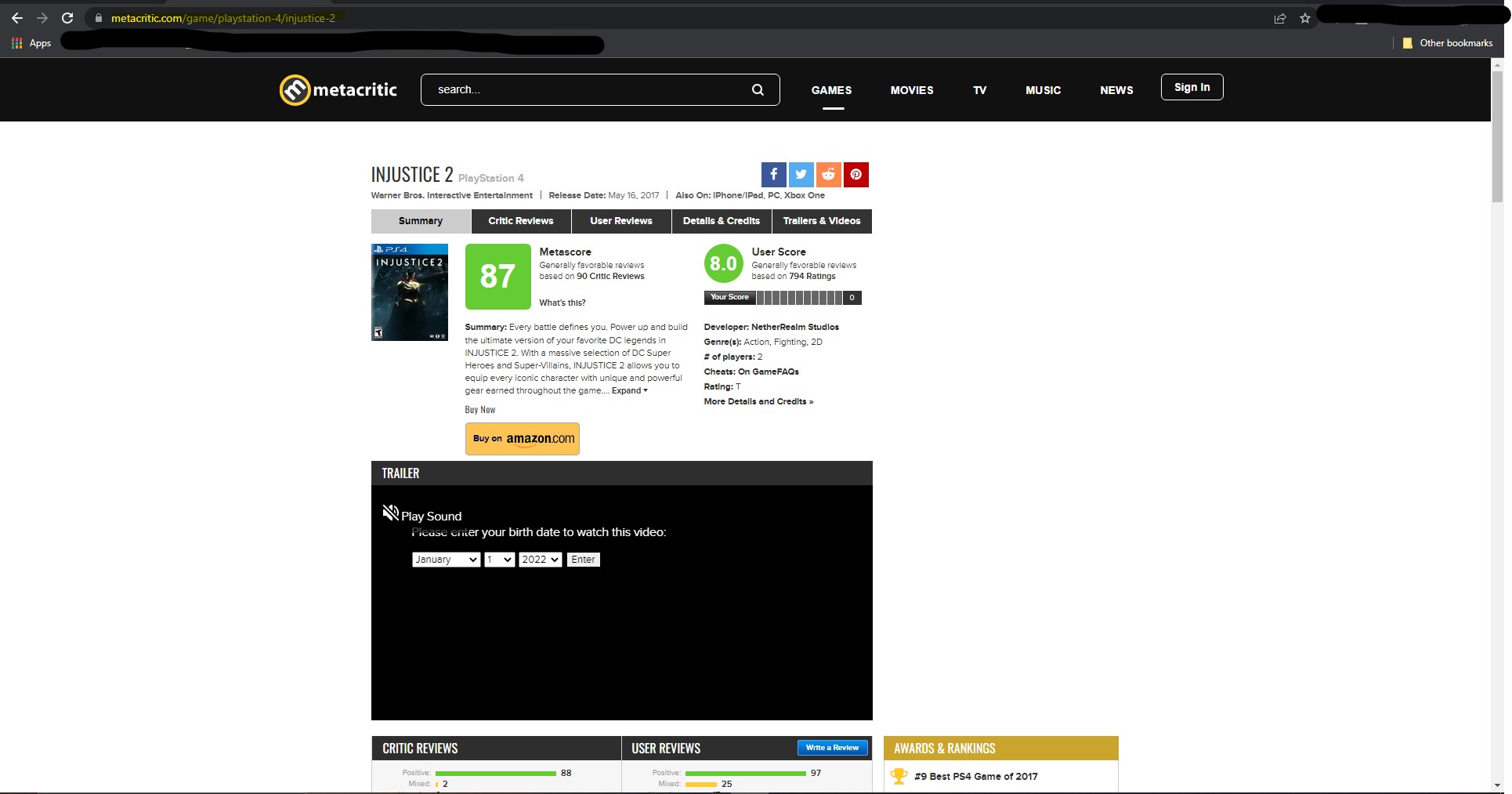

Step 1: Go to the url of interest

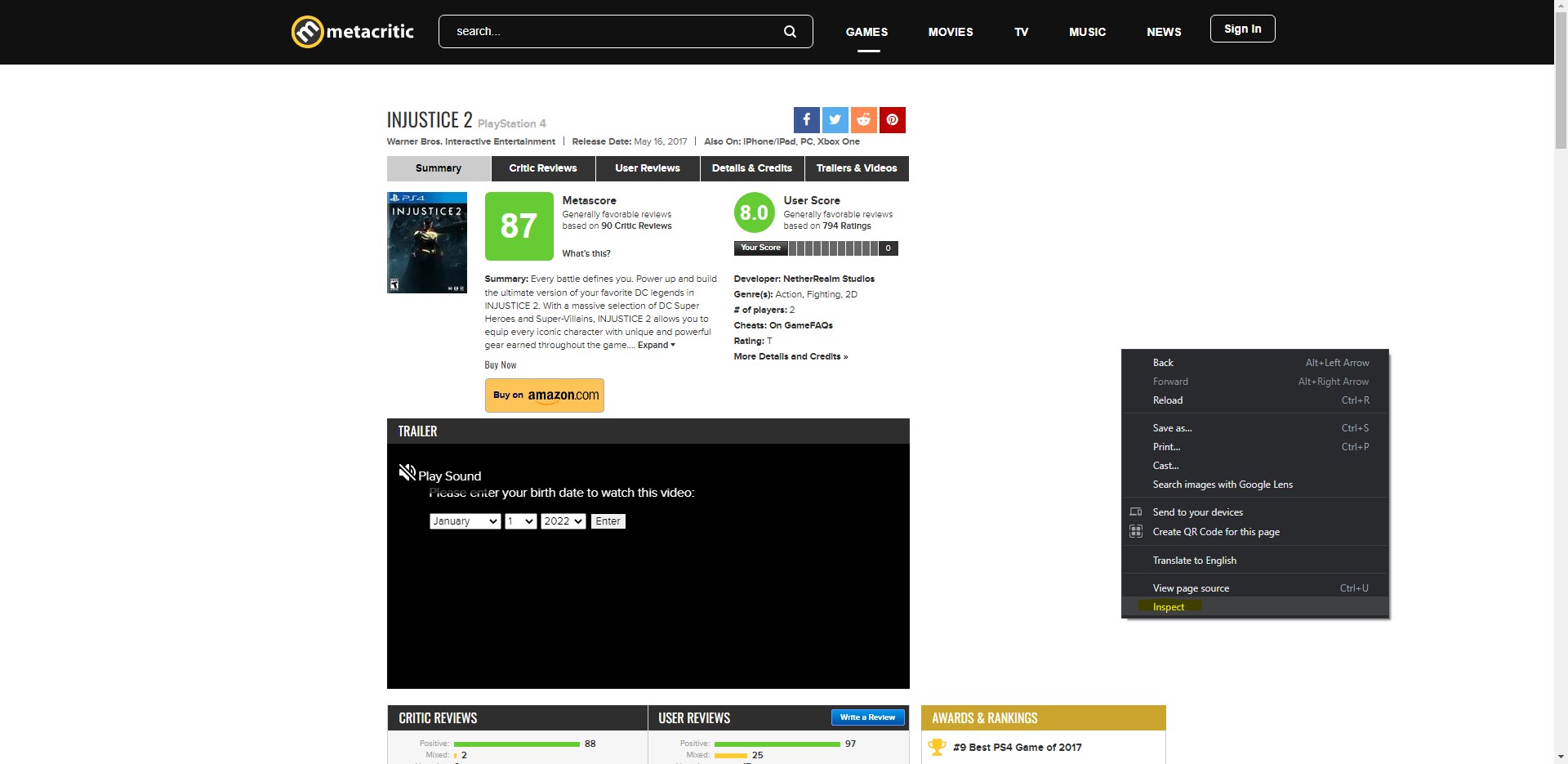

Step 2: Right click anywhere on the page and click on inspect. This will open the chrome dev tools that gives us info about the page and network stats.

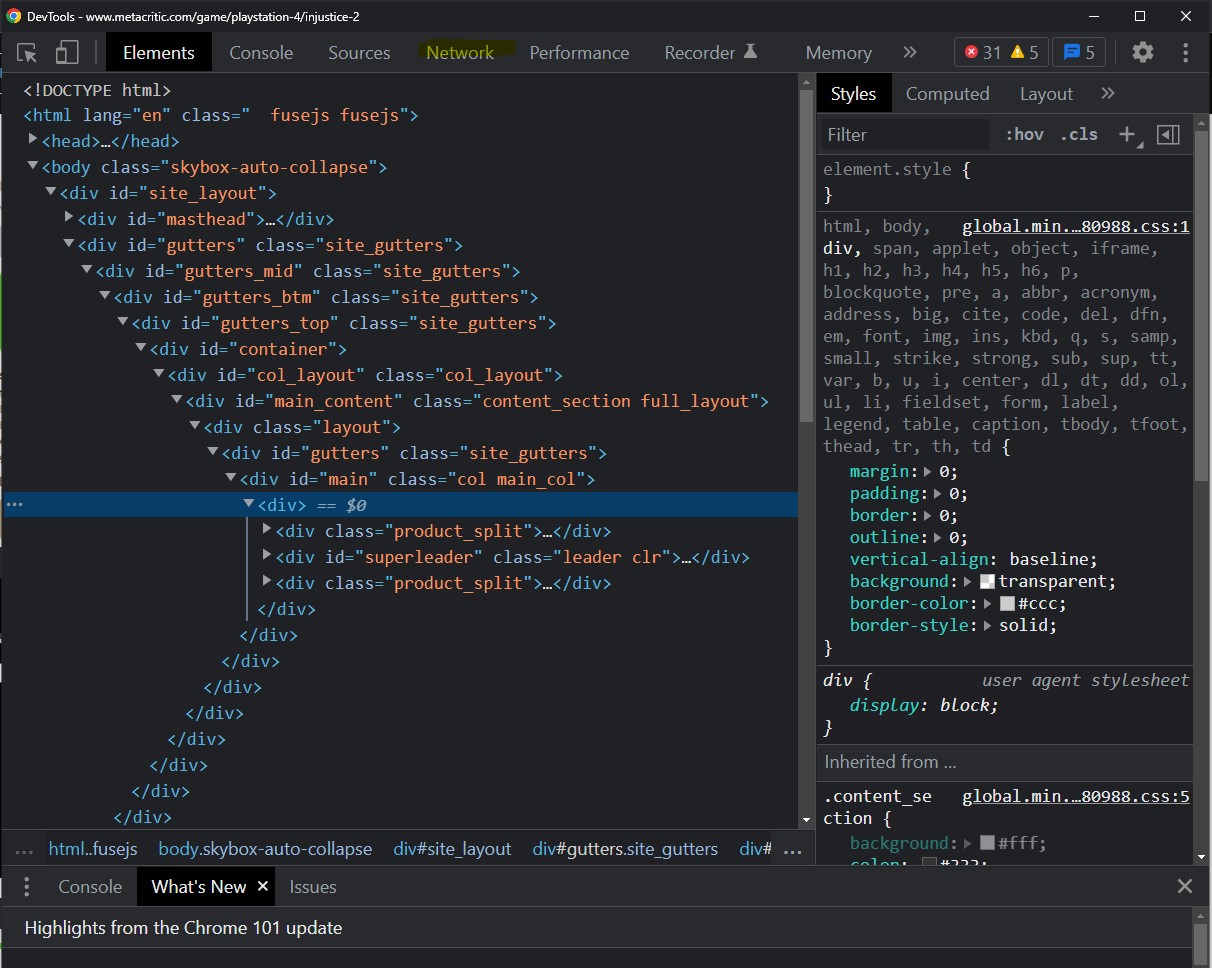

Step 3: You'll notices either a window pops up as part of the browser or off the browser as a separate window. Thats the chrome dev tool. Find the Network tab and click it.

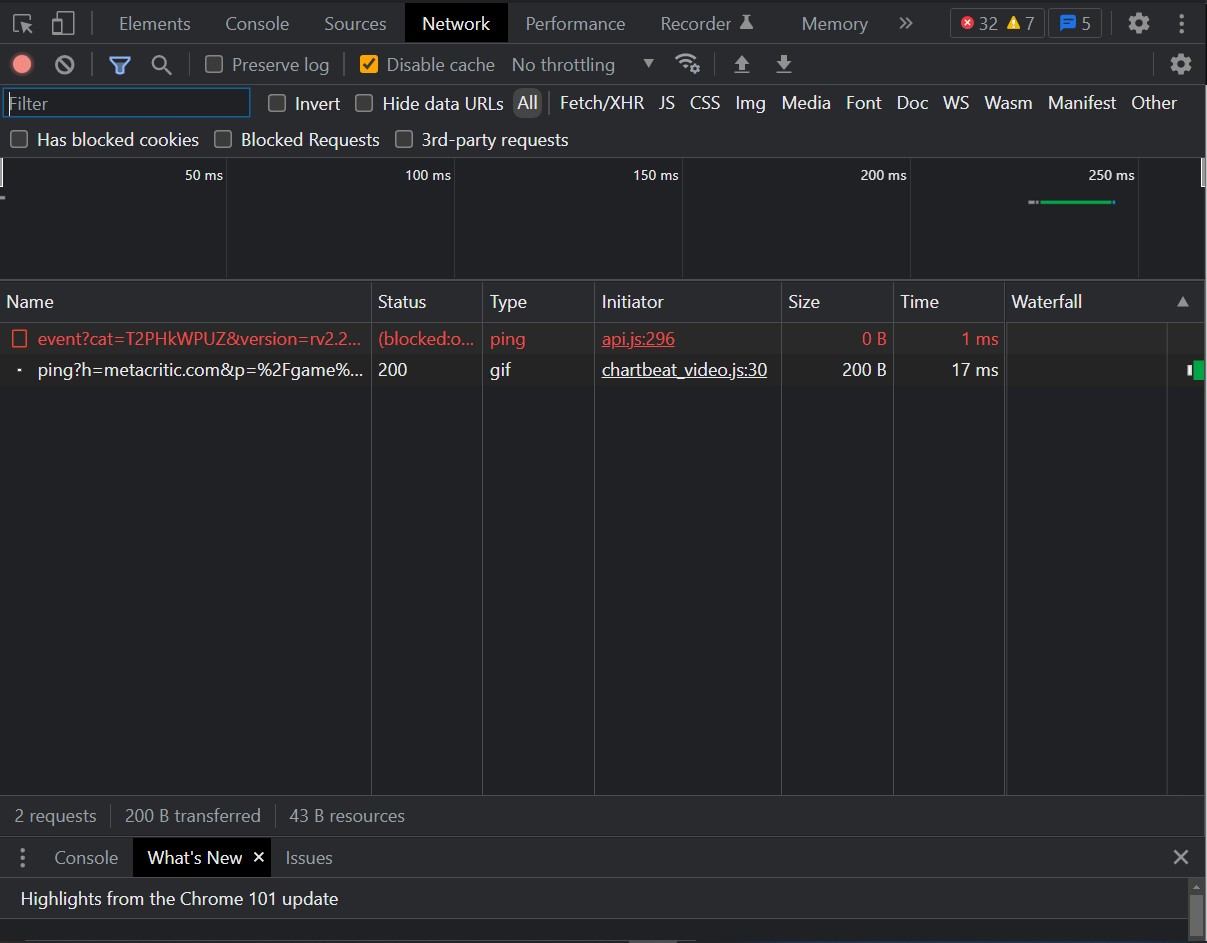

Step 4: You will find a weird tab with a bunch of things on it. We're interested in the lower half of the tab where we see a table with a bunch of columns. One column called Name is the one we're interested in. You might find that it's either empty or has a couple of things, but defintely not many things. We need to refresh the page while the dev tools are open one more time so that we see more things appear in the tab.

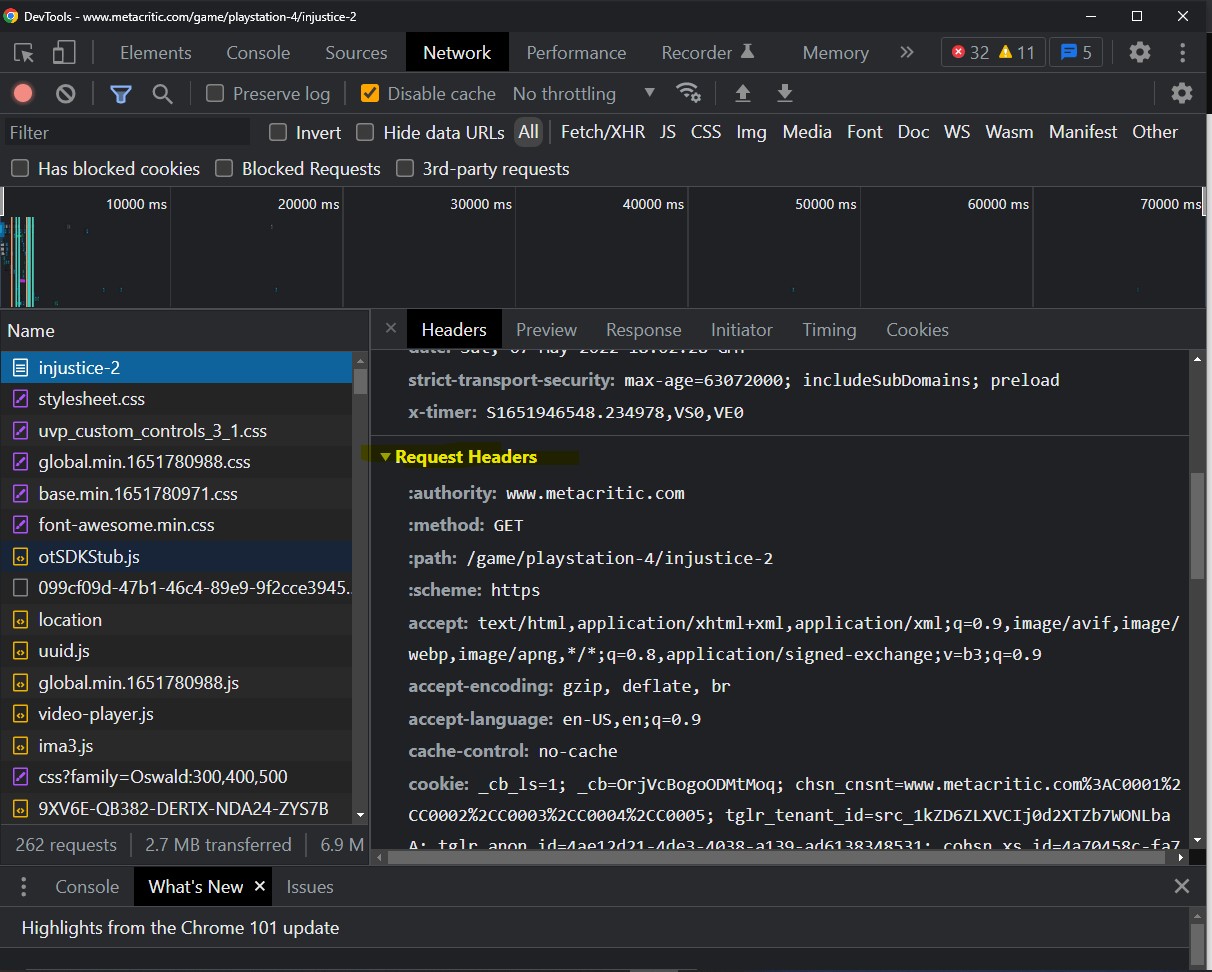

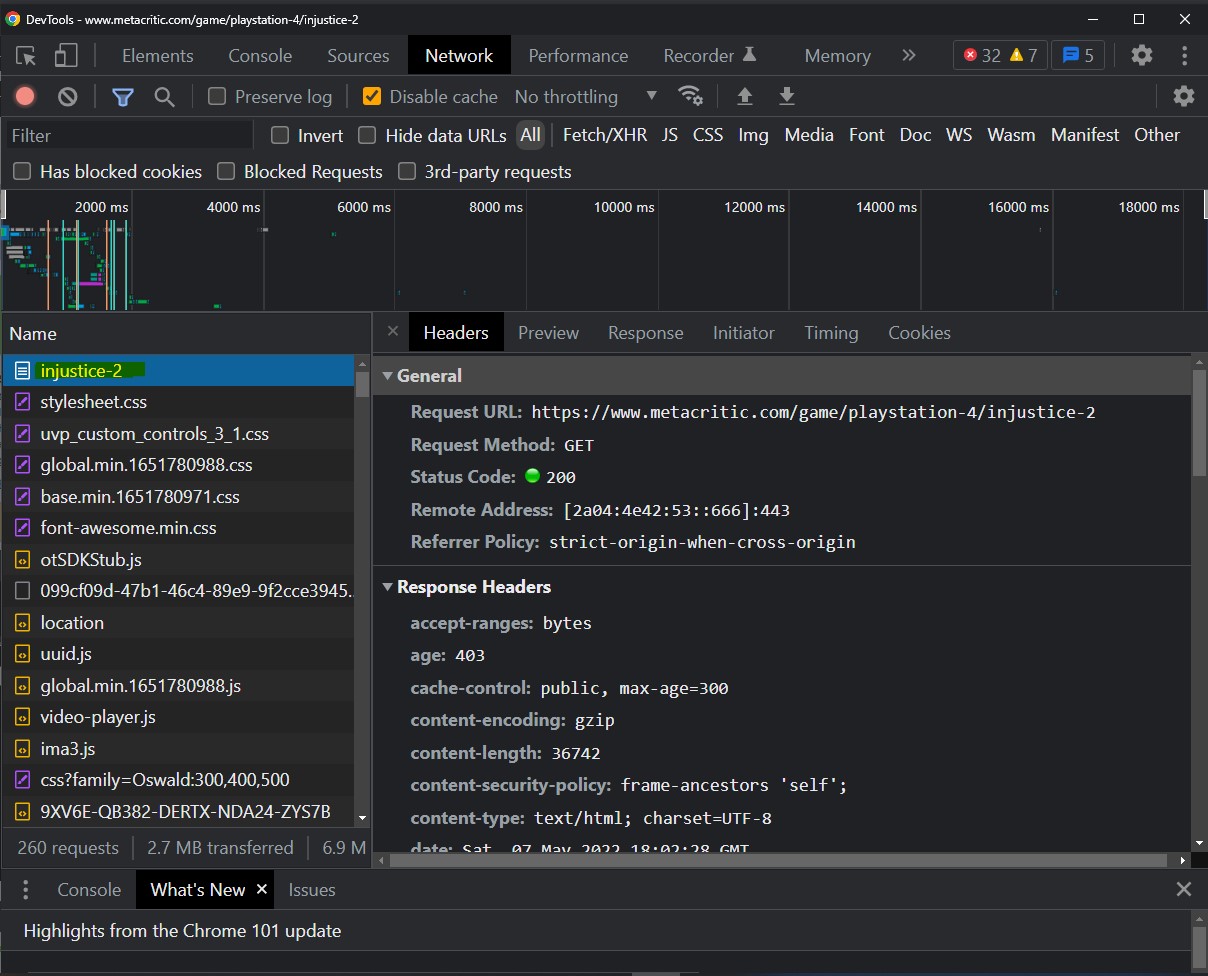

Step 5: The "things" mentioned in step 4 are basically elements of the page that had to travel through the network to be a part of the page like images, the web page itself, some scripts related google ads and what not. We want to find the webpage itself in the Name column. It should have the same name as the game itself. So since we're looking at Injustice 2, it will be called injustice-2. This isn't a convention or anything but that's typically how the webpages are named based on observation from other metacritic pages using the same steps here. Once you locate it, click on it to view information about it. A panel on its right should appear.

Step 6: Scroll down the panel on the right till you find a drop down panel called "Request Headers". This is from which we will be copying our values to put in our own request headers. We do this so that the request we make in the script resembles that of the browser. See the code block below to see what headers I chose to include.